Growing up in the south of France as well as in a castle, my understanding of wealth was shaped by reading stories written by the Comtesse de Ségur, one of the most popular authors of the Bibliothèque Rose, a French literary collection known for its pink children's books. In these tales, set against the backdrop of European aristocracy, being privileged wasn't about money and luxury—it was about responsibility, kindness, good manners, and generosity.

A lesson in charity

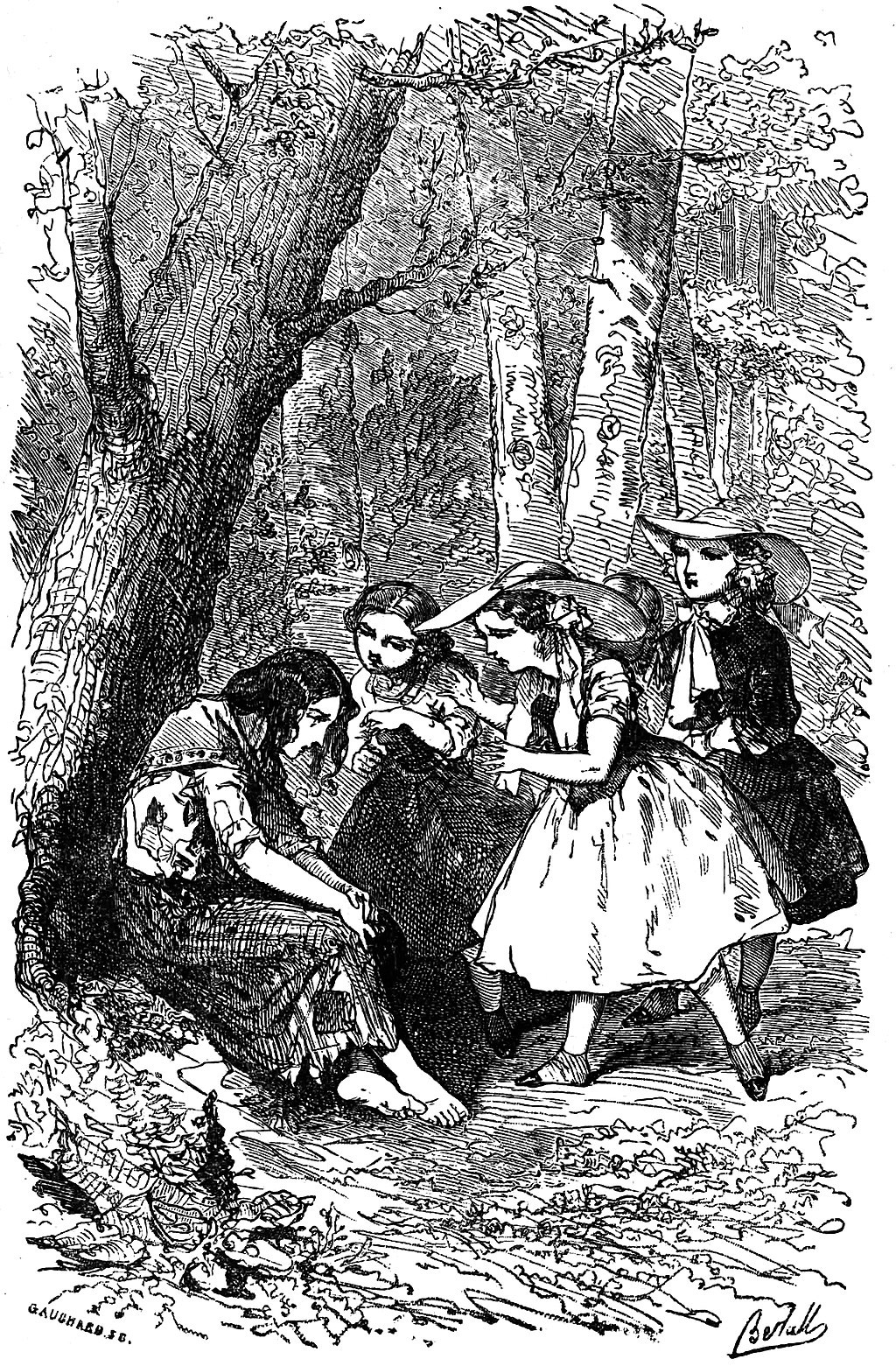

In one scene from "Les Petites Filles Modèles," Madame de Fleurville, the countess of the castle, leads the girls, Camille, Madeleine, Sophie, and their friend Marguerite down a winding path to a cottage at the edge of the estate. They carry baskets filled with bread, cheese, preserved meats, fruits, and a bottle of good wine—provisions for the Hurel family who had fallen on hard times after the father's injury left him unable to work.

"Children," Madame de Fleurville explains as they approach the modest dwelling, "remember that true nobility lies not in what we possess, but in what we share with others. It is our duty to care for those in need."

The girls nod. When they enter the cottage, they are struck by its bareness. Yet the countess shows no discomfort. She greets Madame Hurel and inquires about the family's health and needs. She does so with the same respect and warmth she would show a fellow aristocrat.

What struck me most about this scene was not just the charity itself, but how it was delivered—with dignity and respect rather than virtue signaling.

The little girls weren't merely observing an act of charity; they were being initiated into a tradition of stewardship.

This was the old money I came to admire through these stories. It wasn't just talk or writing a check from a distance; it was genuine action, volunteering, interaction, expression of compassion, care, and relationship.

Interestingly, the author started writing her novels when she was 58, 68 years after the French Revolution began. Perhaps her stories reflected a collective lesson learned.

The changing landscape of wealth

It seems the lessons learned during the French Revolution have been forgotten. Today’s wealthy influencers and their debauched behavior remind me of Louis XVI with his queen Marie Antoinette.

Today's streets are beginning to resemble the 1788 "Day of the Tiles" which saw citizens in Grenoble clashing with authorities, signaling the growing unrest that would eventually culminate in the French Revolution. Interestingly, the crowds protested an administrator who was attempting to abolish the local government to work around their refusal to enact a new tax to deal with France's unmanageable public debt. Sounds familiar? The lower classes were angered by heavy taxation, feudal obligations, and social inequality. Five years later, mass executions with the guillotine during the Reign of Terror began. Perhaps the recent killing of a health insurance executive on the streets of NYC is a sign of more violence to come.

Definition of wealth has changed

For decades, being a millionaire was synonymous with having "made it"—a clear marker of success and wealth.

What constitutes having "made it" today? That benchmark has become increasingly murky. What used to be considered rich now occupies a very different position on the wealth spectrum.

I recognize that referring to millionaires as "middle class" might sound tone-deaf to many readers. To be clear, I'm examining relative positioning within the wealth spectrum, not suggesting millionaires face the same economic challenges as the traditional middle class. Although I am not from the traditional middle class myself (although my Swiss grandparents were), I have friends who were once part of that demographic who now find themselves struggling to survive. Their reality is worlds apart from even the most modest millionaire. The true middle class has been hollowed out, with many falling into financial hardship, while those with millions are simultaneously being dwarfed by the astronomical wealth of billionaires. This two-tiered squeeze—from both directions—is part of what makes our current wealth distribution so concerning.

Given how dramatically wealth distribution has changed, I believe we need to update the definitions that financial advisors currently use:

Mega-wealthy (my proposed term): Those with $1 billion or more (Forbes 400 territory)

Ultra-high net worth individuals (UHNW): People who have an investable net worth of $30 million to $1 billion

High net worth individuals (HNW): People who have an investable net worth of $1 million to $30 million

In case you're wondering, investable net worth doesn't include your home. And secondary homes only count if you rent them out.

The nature of wealth has shifted too. Back in 1988, when I was 18, 30-40% of wealth was in tangible, hard assets, such as real estate, manufacturing, and other physical properties. Today, that number has dropped to 10-20%.

Take the Forbes 400 list, for example. Back when I was 18 (one year after this list began), it wasn't unusual to see names on the list with a net worth in the $200–300 million range. Fast-forward to today, and that list is completely unrecognizable. In 1988 there were 140 billionaires on the Forbes list. Today, there are 3,028. This means there are 2,888 more billionaires today than when I was about to turn 18. That's a 2063% increase.

So not only has there been a shift that has altered the relative positioning of millionaires compared to the ultra-rich, but we've also seen a fundamental change in how net worth is measured.

The very definition of wealth has transformed, revealing not just a widening economic gap, but a shift in values. The notion of "old money"—wealth accompanied by social responsibility—has given way to the worship of power, greed, and political influence. Instead of seeing charity and humanity celebrated on social media, we see narcissistic influencers promoting their luxurious lifestyles.

As we explore this evolution, we might ask ourselves: have we lost something essential in our collective understanding of what it means to be wealthy?

The power of billionaires

Two days ago, Forbes came out with its Trust Fund Fortunes: The World’s Richest Heirs 2025. Topping the list are the Waltons, heirs to an empire that profited during the pandemic. The power that these billionaires wield is immense. Consider the lockdowns during Covid: mega businesses like Walmart and Amazon were deemed "essential" while small mom-and-pop stores selling the same wares were not. I found that terribly unfair.

According to Forbes, about one-third of those 3,028 billionaires inherited "at least a significant part of their fortune."

The case for tax reform

I believe tax laws need to adjust to this dramatic change in wealth distribution. Our current tax system was designed for a different economic landscape—one where the gap between millionaires and billionaires wasn't so vast. Today, with the 2063% increase in billionaires since 1988, exemption levels have become dangerously outdated.

Take estate taxes, for instance. If no changes are made before December 31 of this year, the estate tax exemption of around $5 million for individuals or $10 million for married couples (without counting for inflation) will return. Estates exceeding that threshold face graduated tax rates as high as 55%.

This creates a troubling scenario for those in that grey zone—estates above the threshold who will be forced to sell family homes and farms. This will affect farmers, professionals, business owners, and families who've saved over generations.

The estate tax exemption should be raised proportionally to match the explosion in billionaire wealth—potentially by that same 2063% factor. This would protect families and businesses from being wiped out.

Without these adjustments, we risk creating an even greater divide between the ultra-rich and everyone else.

Rediscovering the true meaning of wealth

As I reflect on wealth today, I find myself returning to those Comtesse de Ségur stories that shaped me. Sadly, I fear we risk losing an understanding of wealth as stewardship. We need a revival of the values that once accompanied wealth: discipline, virtue, restraint, and social responsibility.

In the end, being truly rich has never been about numbers. It's about understanding that with great wealth comes great responsibility—a lesson as relevant today as it was in Europe after the French Revolution, and one we would do well to remember.