The money taboo: Why wealth can feel ugly to those who inherit it

Part 1 of 5: Beyond the Golden Ghetto

I remember sitting around the dinner table one Christmas, back when our family still gathered for the holidays, before the big court case that ended all that.

"It takes one generation to make it, one to spend it, and one to lose it," my uncle said, his voice carrying the weight of experience.

The table fell silent.

At the time, I thought my uncle had created our wealth. Later, I learned that he had built upon the wise investments our great-great-grandfather had made. Still, his words stayed with me, a reminder of wealth's fragility and the pressures it brings.

The pressure paradox

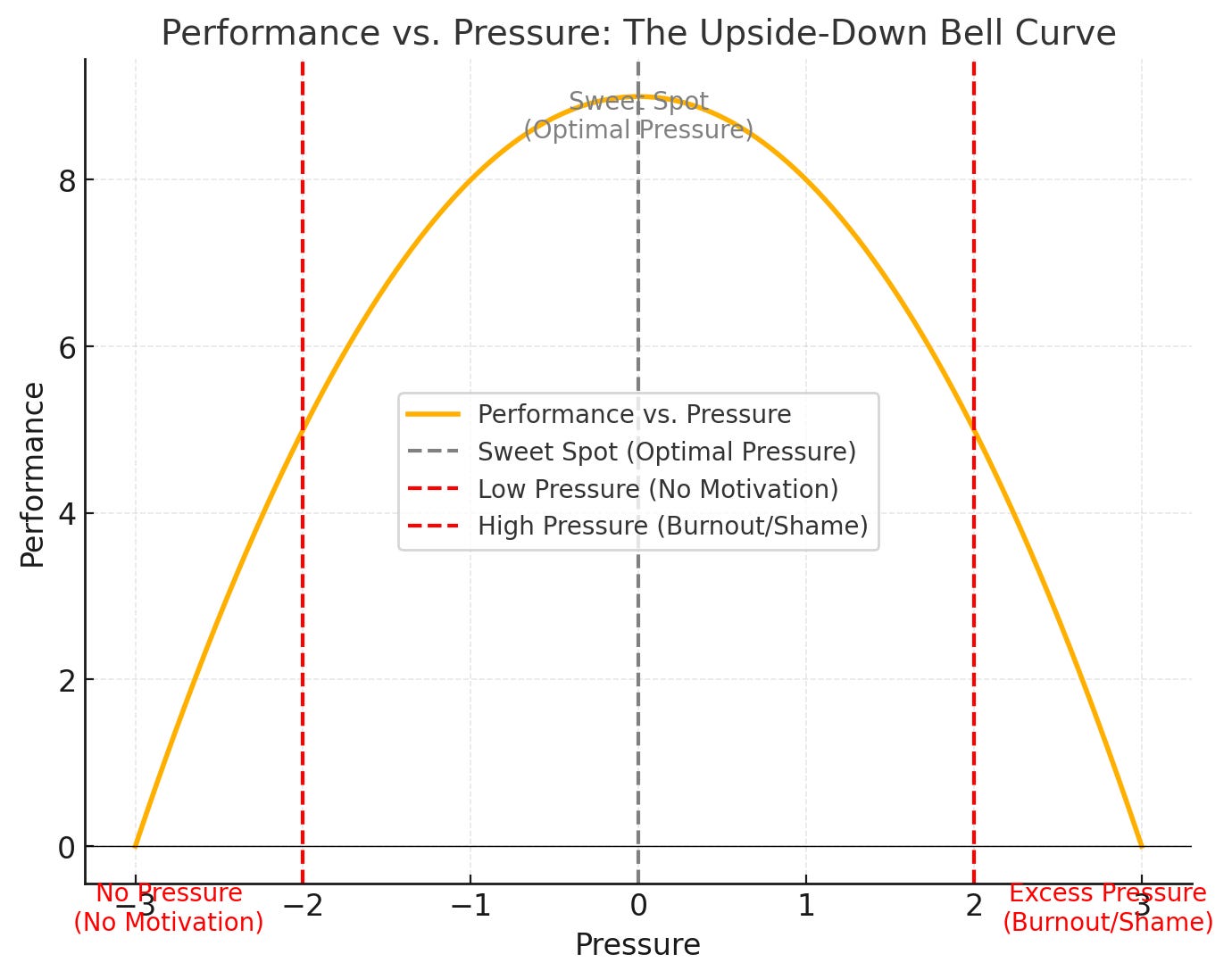

Billie Jean King famously said, "Pressure is a privilege." And she's right—when the pressure is just right. Imagine an upside-down bell curve. On the bottom left corner, there's no pressure: no motivation, no reason to get out of bed, no drive to engage with life's challenges.

As pressure rises, so does performance. This is the "sweet spot"—where challenge feels manageable and motivating. It's here that people thrive.

But beyond this sweet spot, the curve dips. Excessive pressure—rooted in shame, guilt, or impossible expectations—causes performance to falter. On the far right, individuals become so overwhelmed they can't perform at all. Depression, isolation, burnout, substance use, and emotional paralysis take hold.

This curve illustrates the paradox of privilege. Too little pressure, and individuals lose their sense of agency. Too much, and they crumble under unrealistic expectations. The key lies in finding that middle ground where pressure motivates but doesn't overwhelm.

The weight of inherited wealth

For individuals from wealthy intergenerational families, finding this sweet spot proves particularly challenging. The pressures they face are complex, compounding like interest in a bank account:

Isolation breeds difficulty finding friends who understand without judgment.

Privacy and trust issues create emotional walls of constant wariness.

Societal judgment demands proving one's worth and humility.

Self-worth struggles when wealth defines identity; and when well-meaning parents shield children from consequences.

Frequent international moves foster rootlessness, severing ties to place and community.

Mental health suffers as isolation and money enable addiction.

Conformity pressure clashes with some modern values.

Identity confusion taints achievements.

Financial decisions loom large despite advisors and planning.

Legacy expectations stifle personal dreams.

Yet, these pressures are symptoms of a deeper issue—the emotional foundation often missing in families.

The missing foundation

While many focus on identity and purpose—Maslow's higher needs—emotional safety must come first. Wealth often masks neglect through outsourced attachment, i.e. institutions and nannies.

Consider the four-year-old Russian girl in Gstaad who arrived each day alone to daycare by taxi. Her defiant behavior and tendency to run into traffic signaled deep distress. When her father, yachting in the Mediterranean, was contacted, he merely berated the teacher. In less privileged circumstances, social services would have intervened.

These historical attitudes have shaped a cultural legacy of secrecy and shame around wealth, a legacy still alive in modern-day interactions.

Historical legacy

Shame around wealth runs deep. Tokugawa Japan ranked merchants lowest. (Interestingly, it ranked samurai at the top (yay!), followed by farmers and craftsmen.)

Medieval Christianity prohibited usury and condemned profit. Consider the biblical quote: “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” The "eye of the needle" was a gate in Jerusalem—to pass through, a camel had to kneel in humility and shed its bags, symbolizing attachments and character defects.

Even America's Gilded Age aristocrats' disdain for "new money" created secrecy around wealth that persists today. Emotionally damaged inheritors avoid engagement while nouveau riche miss key values for preservation.

Today’s reality

At a Newport party 20 years ago, an older man—who "never worked a day in his life"—sneered and said "I'm so sorry" when a family member announced his new job as an analyst at a prestigious real estate firm.

Just last week, a client, whose family fortune vanished through "misadventures and delusions, bad investments, carelessness," and who congratulated me for "having the courage to speak about this taboo" is now rebuilding his wealth. I am confident that through his industry and resolution, he’ll succeed and I root for him.

By the way, I mentioned last week that while I’m currently all booked up at the moment, I’m opening up a handful of spots to work with new clients at the start of the new year. I wanted to let you know that if you’re not already on the waitlist and this is something that you might be interested in, here’s the link to get yourself on the waitlist now.

Besides strained relationships, how money should be spent, saved, or given provide fertile ground for friction.

At 13, I discovered a book left by a British houseguest and read it in one day. It was called Class: A Guide Through the American Status System by Paul Fussell. The book confirmed what I innately knew that showing too much wealth was considered “declassé.”

But it’s not just it’s display. There is a more insidious aspect to wealth that undermines health. It’s called hyper-agency.

Hyper-agency—wealth's ability to avoid all friction—erodes resilience, as Dr. Paul Hokemeyer writes about. After my Gstaad neighbors fled rainy days by private jet, their house manager confided to me that the couple seemed perpetually miserable, seeking external solutions to internal problems.

Historical wisdom

Some historical figures recognized wealth’s dangers.

Michel de Montaigne’s father sent his young son to live with peasants, teaching simplicity and humility before returning to the château. This grounding influenced his later essays on how to live a meaningful life.

Similarly, in Confessions, Leo Tolstoy admires the common peasants he encountered in Russia. He found meaning in peasants' groundedness and resilience—qualities that eluded the elite of the day.

These lessons remain relevant. Shielding children from hardship and simplicity doesn’t prepare them for a meaningful life. Instead, it disconnects them from experiences that build self-worth and resilience.

This explains why rags-to-riches stories resonate: struggle fosters growth or antifragility.

The path forward

A man of simple beginnings, Benjamin Franklin, wrote about his favorite 13 Virtues—temperance, silence, order, resolution, frugality, industry, sincerity, justice, moderation, cleanliness, tranquility, chastity and humility.

These virtues remind us that wealth need not define us—it can be a tool for growth. For example, industry and resolution can counter feelings of isolation, while frugality and order provide a framework for managing wealth responsibly.

Breaking taboos and to the horror of my friends, we used to discuss money as well as sex and politics at table. Mother taught more than checkbook balancing; she stressed only spending interest and not touching capital. Money in the hands of a woman was even seen as insurance against an abusive marriage. I later learned through experience that attachment bonds prove stronger than wealth.

The privilege paradox requires finding motivation's sweet spot—where pressure energizes rather than paralyzes

.

Money isn’t good or bad—it just magnifies the shame or willingness that’s already there.

To learn more about Diana and her work, visit her website.

Insightful and well-written!